It is the spring of 1943. The tides of war are shifting, but slowly, and not without price. Across the vast reaches of the Pacific, the United States Navy’s submarine force is waging an invisible war, slipping silently beneath enemy shipping lanes, severing supply chains one torpedo at a time. These boats are not the sleek, nuclear-powered giants of later decades, but diesel-electric beasts with steel hulls and sweat-stained decks. Their crews, young and dogged, live and die in a steel tube barely longer than a football field. It is here, in this crucible of pressure and silence, that the USS Kingfish (SS-234) earned her scars—and her survival.

It is the spring of 1943. The tides of war are shifting, but slowly, and not without price. Across the vast reaches of the Pacific, the United States Navy’s submarine force is waging an invisible war, slipping silently beneath enemy shipping lanes, severing supply chains one torpedo at a time. These boats are not the sleek, nuclear-powered giants of later decades, but diesel-electric beasts with steel hulls and sweat-stained decks. Their crews, young and dogged, live and die in a steel tube barely longer than a football field. It is here, in this crucible of pressure and silence, that the USS Kingfish (SS-234) earned her scars—and her survival.

By March of 1943, the submarine war in the Pacific had entered a critical phase. The Imperial Japanese Navy, while still formidable on paper, was beginning to feel the sting of American undersea warfare. Shipping losses were mounting. Japan, an island nation with far-flung conquests, depended on maritime lifelines for oil, rubber, rice, and reinforcements. American submarines, emboldened by improved torpedoes and hard-won experience, had become the scalpel slicing those lifelines. But the enemy was adapting. Convoys were better guarded, air patrols were heavier, and depth charges—those merciless steel drums of doom—rained down with increasing accuracy.

American subs, for their part, had become bold and blooded. And none more so than the USS Kingfish.

Kingfish was a Gato-class submarine, the workhorse of the wartime fleet. Commissioned in May of 1942, she had not wasted time. Her first patrol took her to the coast of Japan itself, where she landed her first kills and survived an 18-hour gauntlet of depth charging. Her second patrol proved equally aggressive: she sank freighters, shelled trawlers, and tangled with the wily enemy escorts who knew just where to look for a submerged threat.

By the time she slipped her lines on February 16, 1943, bound for her third war patrol, she was no longer green. She had teeth—and the men aboard her knew how to use them. Her skipper, Lieutenant Commander Vernon “Rebel” Lowrance, was one of the finest. He was calm in crisis, daring but not reckless, and respected by his crew. This third patrol would take them to the treacherous waters off Formosa (modern-day Taiwan), a known hotbed of Japanese military traffic. What they found there, however, was not just prey—but peril.

The attack came in the early morning darkness of March 23, 1943. Kingfish was stalking what her crew initially believed to be a destroyer, later confirmed to be the Japanese minelayer Sokuten. She had gotten into a good position, angling for a torpedo shot in the predawn gloom, when the target turned the tables. Whether they caught sight of Kingfish’s periscope or picked up a faint sonar echo, the Japanese ship came straight for her at sixteen knots.

Kingfish bolted. She went to flank speed, a maneuver that risked giving away her position, but necessity outweighed stealth. When the searchlight stabbed out across the water and caught her at 5,500 yards, there was no mistaking it: they had been seen. There would be no shot that morning. Rebel Lowrance took her down.

She dove to 250 feet and rigged for depth charge attack—one of those understated phrases that, to a submariner, meant cinching your gear tight, silencing every machine, and waiting to see if you would live through the hour. For a time, they thought they had lost their hunter. But at 4:48 AM, the sea exploded.

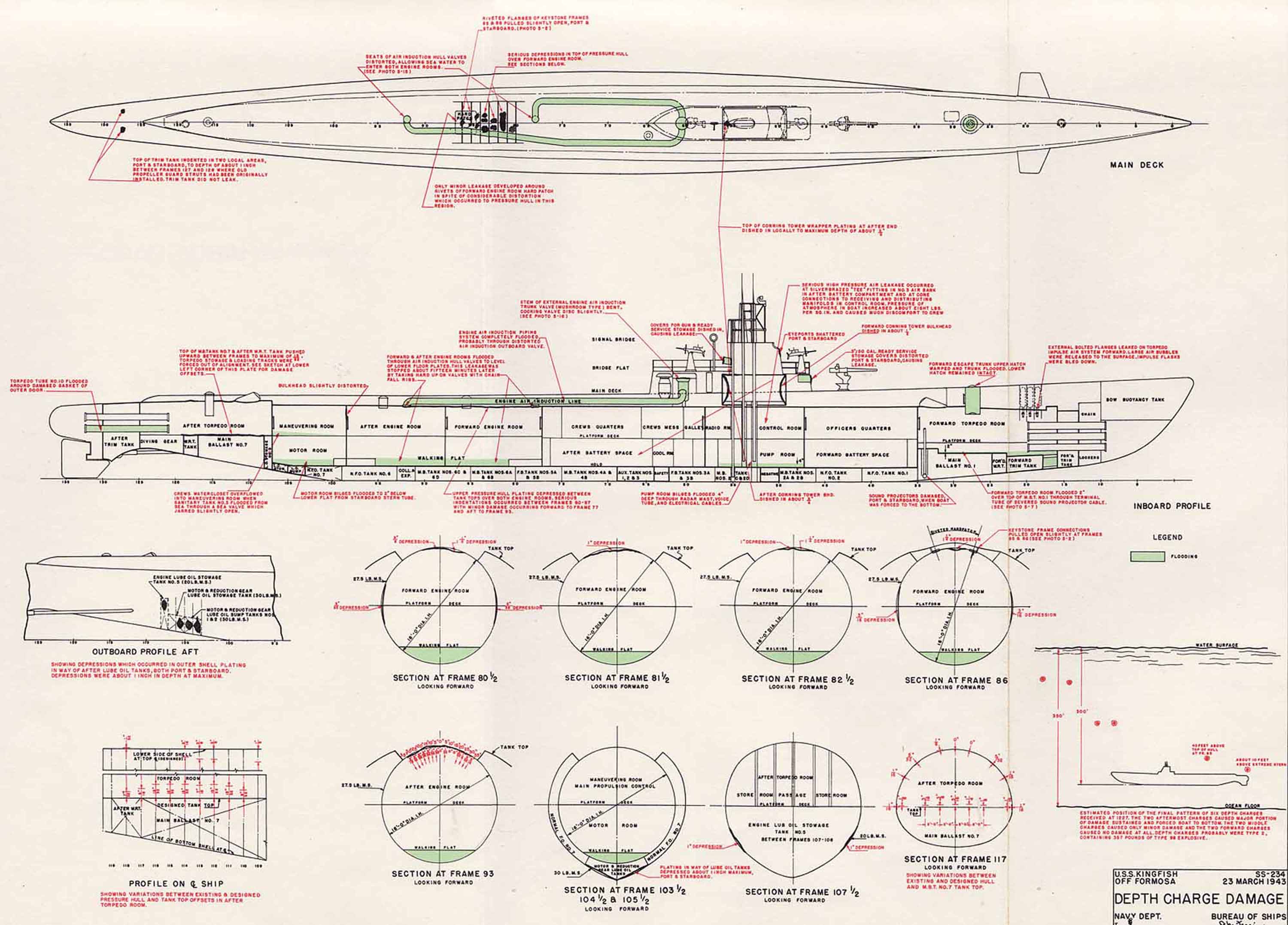

The first charges came in fast. Over the next eight hours, the enemy made eight separate runs, dropping a total of 40 depth charges. Most fell close—between 25 and 150 yards—and in submarine warfare, that is terrifyingly near. Each blast was a body blow. Steel groaned. Lights flickered. The air stank of oil and sweat and fear. Kingfish dropped deeper—to 300 feet in 350 feet of water—and turned slowly, quietly, trying to throw her pursuers off.

At 7:52 AM, the screws of another ship joined the hunt. Now there were two of them. They pinged relentlessly, sonar pulses bouncing off her hull like a hammer on a drum. Twice Kingfish tried to rise to 200 feet, hoping to line up a shot with her torpedoes. But both times, the enemy sensed her movement and came in hot, rolling more depth charges into the dark.

By early afternoon, the situation was dire. For hours, she had endured. Her hull had held. Her crew had held. But fate, like pressure, has its limits.

At 12:27 PM, the enemy made one final, perfect pass. Two depth charges landed practically on top of her engine room—at a gut-churning estimate of 25 to 50 feet. The shockwave caved in the hull plating above the engine spaces by four inches. That might not sound like much, but in a submarine hull, it is enough to break systems and men alike. Worse, it bottomed them out. Kingfish hit the seafloor at 350 feet. And then, the worst kind of water began to come in—not in a spray, but in a steady trickle, from hull flappers that no longer sealed.

The crew moved fast. They rigged chain falls across the damaged valves to stop the leaks. They silenced everything. They sat in stillness and shadow as the enemy listened overhead. They burned their confidential codes. They disabled their TDC (Torpedo Data Computer), lest it fall into enemy hands. Even their sonar heads were knocked out of line.

For the next six hours, they played dead. Plans were drawn to scuttle the boat. Battle stations were manned for what might be the final time. At 6:30 PM, just before dusk, they readied the charges. They would not be captured.

Then, at 6:48 PM, with the sea dark and rough and the enemy seemingly gone, Kingfish rose to the surface. There, about 2,000 yards off her starboard bow, loomed a Japanese patrol vessel, lying quietly in wait.

There was no time for subtlety.

Kingfish ran. She pushed her four diesel engines to flank speed and raced out of the area, a wounded beast limping through the waves. By 8:00 PM, she began to recharge her batteries. By 10:00 PM, her bilges were dry. The next morning, she dove again, still leaking, still damaged, but alive.

She stayed under until the 26th, then made a break for Midway. On April 4, she arrived, battered but unbroken. Her crew, no longer merely experienced, were now veterans forged in steel and saltwater. Four days later, she departed under escort for Pearl Harbor. By April 9, she was back in American hands. Home, for now.

The story of Kingfish did not end in that depth charge crater.

After her repairs at Mare Island—where whole sections of her hull were rebuilt—Kingfish returned to the war. She completed twelve war patrols in total, earning nine battle stars and sinking fourteen enemy vessels totaling over 48,000 tons. She planted mines, conducted special missions, and rescued British aviators. She dodged bombs, battled convoys, and struck fear into Japanese shipping from Formosa to Borneo. In one war patrol, she put three tankers on the bottom in a single week.

She was not the most famous of the fleet boats, but she was one of the finest. Her survival on March 23, 1943, was not a matter of luck. It was grit, skill, leadership, and no small amount of divine mercy. To the men who served aboard her, she was more than a war machine—she was home, and she brought them back.

Kingfish was decommissioned in March 1946 and eventually sold for scrap in 1960. But her legacy lives on in the hearts of the men who served beneath the waves and in the annals of the Silent Service. For those who have heard the thunder of depth charges and felt the groan of a hull under pressure, Kingfish’s story is not just history. It is brotherhood. It is survival. And it is the reason that, even today, submariners still say: there are two kinds of ships—submarines, and targets. Kingfish proved which one she was.

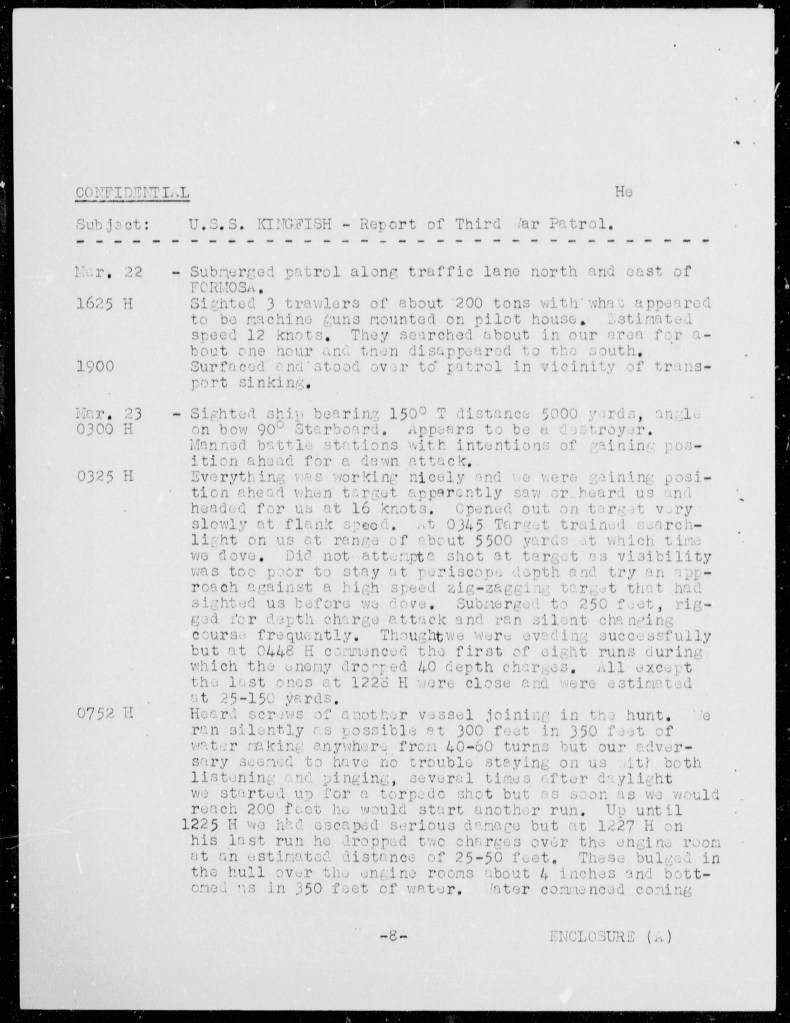

The incredibly understated deck log from the USS Kingfish SS-234 for March 23, 1943 (National Archives)

Leave a comment