The Cold War had officially ended, but the deep, frigid waters of the Barents Sea still played host to a silent and deadly chess match between American and Russian submarines. It was March 1993, and while Boris Yeltsin and Bill Clinton were preparing for their first presidential summit, the military forces of their respective nations were still adjusting to a new geopolitical reality. The Soviet Union had collapsed barely a year earlier, and Russia was struggling to maintain control over its vast nuclear arsenal, a situation that deeply concerned the United States. The old habits of submarine espionage did not die with the Soviet flag, and American attack submarines continued their missions near Russian bases, shadowing ballistic missile submarines, or “boomers,” that carried enough nuclear firepower to reshape the world in an instant.

The Cold War had officially ended, but the deep, frigid waters of the Barents Sea still played host to a silent and deadly chess match between American and Russian submarines. It was March 1993, and while Boris Yeltsin and Bill Clinton were preparing for their first presidential summit, the military forces of their respective nations were still adjusting to a new geopolitical reality. The Soviet Union had collapsed barely a year earlier, and Russia was struggling to maintain control over its vast nuclear arsenal, a situation that deeply concerned the United States. The old habits of submarine espionage did not die with the Soviet flag, and American attack submarines continued their missions near Russian bases, shadowing ballistic missile submarines, or “boomers,” that carried enough nuclear firepower to reshape the world in an instant.

USN photo # 219796-3-87, courtesy of Darryl L. Baker.

This kind of underwater surveillance had been standard practice for decades. It was part of a strategy known as Operation Holy Stone, a classified program under which U.S. Navy submarines lurked off the coasts of Soviet bases, recording acoustic signatures, tracking missile tests, and collecting intelligence. The Sturgeon-class USS Grayling (SSN-646) was one of these silent hunters. Launched in 1967 and commissioned in 1969, Grayling was an aging workhorse, designed to prowl the depths and gather intelligence undetected. That mission, however, came with risks. The previous year had already seen one such risk materialize when the USS Baton Rouge collided with the Russian submarine B-276 Kostroma just off the Kola Peninsula. That accident had been a diplomatic embarrassment, but it had not deterred further operations.

The Barents Sea, with its shallows, shifting temperatures, and noisy underwater environment, was not an easy place to track submarines. Sound behaved erratically, bouncing off layers of water at different temperatures and salinity. On the night of March 20, 1993, Grayling was tailing K-407 Novomoskovsk, a Delta IV-class ballistic missile submarine of the Russian Navy. Novomoskovsk was not just any submarine; it had made history in 1991 by successfully launching all sixteen of its nuclear ballistic missiles in rapid succession during a test. It was the pride of the Russian Northern Fleet and a crucial part of Russia’s strategic deterrence.

At the time of the incident, Novomoskovsk was on a routine training mission, cruising at a depth of about 76 meters (249 feet), preparing to head back to port in Severomorsk. Grayling, commanded by Cdr. Richard Self, had been shadowing the Russian submarine for hours, keeping a watchful eye on its movements. But then something went wrong. The American submarine lost contact with its target, a perilous situation in these waters. As in any good spy thriller, when a pursuer loses its mark, it has to act quickly to reacquire the target. Grayling accelerated and turned in an attempt to regain sonar contact with the Russian boomer.

By the time Grayling detected Novomoskovsk again, it was already too late. The two submarines were on a collision course, closing the distance at a combined speed of roughly 29 to 37 mph. The American crew had less than a minute to react, and while they attempted to veer off, the sheer momentum of the submarine made that impossible. At 12:46 AM, Grayling scraped against the upper starboard bow of Novomoskovsk, sending a screeching metallic vibration through both vessels. For a moment, no one knew if the worst had happened—if the Russian submarine had been critically damaged or if a missile compartment had been breached. Had the impact occurred just a few seconds later, Grayling might have struck Novomoskovsk directly on its missile bay, a scenario that could have had catastrophic consequences.

The immediate aftermath was a mix of confusion and relief. Both submarines quickly assessed their damage. Miraculously, neither had suffered any life-threatening breaches. The Novomoskovsk had a long scratch and a minor dent on its hull, while Grayling had sustained only superficial damage. Nevertheless, the implications of the collision were enormous. Grayling turned and made sure that Novomoskovsk was still operational before slinking away into the darkness, heading home.

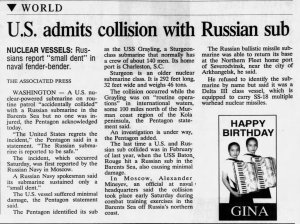

Back on land, the diplomatic fallout was immediate. The timing of the incident could not have been worse—Clinton and Yeltsin were about to meet for the first time, and this collision served as an awkward reminder that the end of the Cold War had not eliminated Cold War-era tensions. Yeltsin was furious, and Russian officials made it clear that they considered the continued U.S. surveillance operations near their waters unacceptable. Clinton, in an effort to smooth relations, publicly apologized and promised an inquiry. However, behind closed doors, the U.S. Navy was reluctant to give up its long-standing practice of monitoring Russian submarine activity.

Back on land, the diplomatic fallout was immediate. The timing of the incident could not have been worse—Clinton and Yeltsin were about to meet for the first time, and this collision served as an awkward reminder that the end of the Cold War had not eliminated Cold War-era tensions. Yeltsin was furious, and Russian officials made it clear that they considered the continued U.S. surveillance operations near their waters unacceptable. Clinton, in an effort to smooth relations, publicly apologized and promised an inquiry. However, behind closed doors, the U.S. Navy was reluctant to give up its long-standing practice of monitoring Russian submarine activity.

Following the collision, U.S. submarine operations in the Barents Sea were scaled back, and new protocols were introduced to minimize the risk of another such incident. Improved sonar tracking procedures, changes in shadowing tactics, and enhanced training for submarine crews were implemented to reduce the likelihood of losing contact with a target and then having to rush to reacquire it. However, the fundamental strategy of tracking Russian boomers did not change.

As for the submarines themselves, Grayling continued to serve for a few more years but was decommissioned in 1997, later scrapped as part of the Navy’s recycling program. Its sail remains on display at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard as a memorial. Novomoskovsk, on the other hand, remained in service and continued to play a role in Russia’s nuclear deterrence. It was modernized and, as of the 2020s, was still listed as active in the Russian Navy. It even participated in launching commercial satellites, a remarkable second act for a vessel designed for nuclear war.

The March 1993 collision between Grayling and Novomoskovsk stands as a reminder of how Cold War habits die hard. Even as politicians toasted to a new era of cooperation, their submarines were still playing the same dangerous game in the deep. It was a near-miss—one of many in the shadowy history of underwater espionage. If nothing else, it serves as a testament to the skill of submarine crews on both sides who, despite the immense risks, kept these incidents from turning into full-scale disasters.

Leave a comment