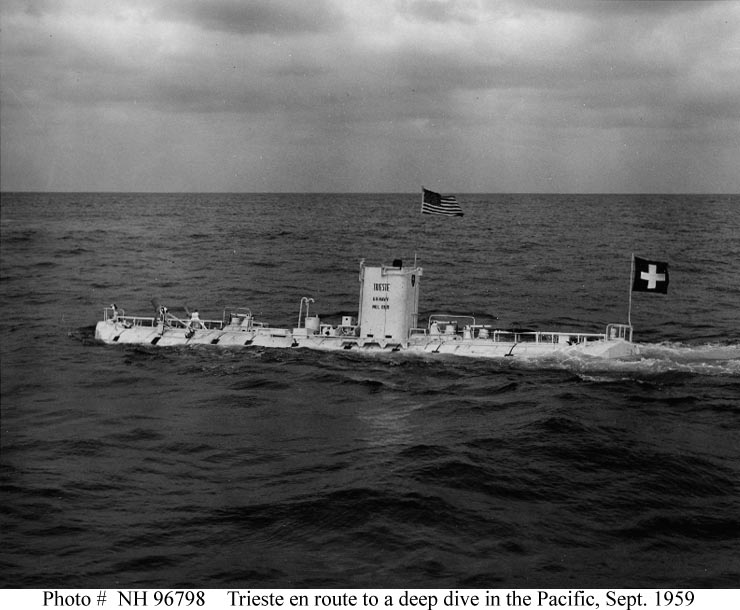

The Bathyscaphe Trieste was no ordinary vessel; it was the culmination of years of ingenuity, ambition, and engineering brilliance. The brainchild of Swiss physicist Auguste Piccard, a man renowned for breaking altitude records in balloons, the bathyscaphe represented a leap from the skies to the depths of the oceans. Inspired by his ballooning expertise, Piccard envisioned a submersible capable of plunging untethered into the darkest recesses of the sea, applying the principles of buoyancy and pressure resistance he had perfected in the air. Working with his son, Jacques Piccard, he constructed three bathyscaphes between 1948 and 1955, one of which set a record by reaching 10,000 feet. The final product, the Trieste, was launched near Capri in 1953 and was later acquired by the U.S. Navy in 1958 to push the boundaries of ocean exploration further.

The Bathyscaphe Trieste was no ordinary vessel; it was the culmination of years of ingenuity, ambition, and engineering brilliance. The brainchild of Swiss physicist Auguste Piccard, a man renowned for breaking altitude records in balloons, the bathyscaphe represented a leap from the skies to the depths of the oceans. Inspired by his ballooning expertise, Piccard envisioned a submersible capable of plunging untethered into the darkest recesses of the sea, applying the principles of buoyancy and pressure resistance he had perfected in the air. Working with his son, Jacques Piccard, he constructed three bathyscaphes between 1948 and 1955, one of which set a record by reaching 10,000 feet. The final product, the Trieste, was launched near Capri in 1953 and was later acquired by the U.S. Navy in 1958 to push the boundaries of ocean exploration further.

The Trieste’s unique design combined a robust pressure sphere with buoyancy tanks filled with gasoline, an incompressible liquid crucial for withstanding deep-sea pressures. Its steel sphere, forged by Germany’s Krupp Works and retrofitted with precision by Swiss engineers, was capable of withstanding the crushing forces at depths exceeding 35,000 feet. This revolutionary design allowed the vessel to function as a self-contained exploratory craft, untethered and free to navigate the ocean’s vast depths.

In the late 1950s, as Cold War tensions heightened, the U.S. Navy recognized immense strategic value in developing technology for deep-sea exploration, including submarine rescue. The acquisition and subsequent refitting of the Trieste by the Navy marked the beginning of a new era in deep-sea exploration and set the stage for one of humanity’s most daring expeditions—Project Nekton.

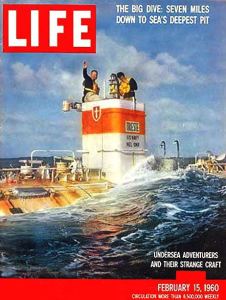

The morning of January 23, 1960, was fraught with anticipation as the Philippine Sea’s choppy waters buffeted the Trieste and her support ships. Jacques Piccard and U.S. Navy Lieutenant Don Walsh, the two-person crew, prepared for what would become an unparalleled journey into Challenger Deep, the deepest part of the Mariana Trench. With the vessel ready, they began their descent at 8:23 a.m., sinking at a steady rate of approximately 0.9 meters per second. The 50-ton bathyscaphe plunged steadily into the vast, inky blackness of the ocean. Hours passed in tense silence, broken only by occasional updates to the support vessel via sonar.

At approximately 30,000 feet, disaster nearly struck. A sharp, resonating crack echoed through the vessel, jolting Walsh and Piccard. For a moment, they feared their lives might end. Later analysis revealed that a Plexiglas outer pane had cracked under immense pressure exceeding 16,000 psi. The terrifying sound and sudden impact heightened the stakes of their descent, but the pair decided to press on.

After a grueling 4 hours and 47 minutes, they reached the seabed. At a depth of 35,814 feet, they observed a barren, oozy expanse illuminated by the bathyscaphe’s quartz arc lights. The temperature inside the sphere was a chilly 7°C (45°F), and the outside world was a silent, featureless void. To their astonishment, Piccard and Walsh reported seeing a flatfish-like creature and shrimp scuttling across the ocean floor, a sight that challenged existing scientific beliefs about life at such extreme depths. Though these observations were later disputed by marine biologists, they underscored the groundbreaking nature of the dive.

The team spent only 20 minutes on the ocean floor before initiating their ascent. Ballast tanks were emptied of iron shot, and the Trieste began its slow return to the surface. After three hours and fifteen minutes, they emerged to a hero’s welcome, completing humanity’s first journey to the deepest known point on Earth.

The team spent only 20 minutes on the ocean floor before initiating their ascent. Ballast tanks were emptied of iron shot, and the Trieste began its slow return to the surface. After three hours and fifteen minutes, they emerged to a hero’s welcome, completing humanity’s first journey to the deepest known point on Earth.

The Trieste’s Challenger Deep dive marked a turning point in oceanography and engineering. Although the vessel itself was rudimentary by modern standards—it carried no scientific instruments and could not collect samples—it proved the feasibility of human exploration in the deep ocean. The mission also demonstrated the courage and ingenuity required to confront the most formidable challenges of nature.

Following the historic dive, the Trieste underwent modifications and served in critical missions, including the search for the USS Thresher in 1963. After several dives, the bathyscaphe located debris from the sunken nuclear submarine at a depth of 8,400 feet, aiding the Navy’s investigation into the tragedy. This mission highlighted the Trieste’s enduring value as a tool for underwater exploration and recovery.

After her operational career, the Trieste retired to a quieter life. She was displayed at various locations before finding her permanent home at the US Naval Undersea Warfare Museum in Keyport, WA. Today, she stands as a testament to human curiosity, resilience, and ingenuity, a silent witness to one of the greatest achievements in exploration history.

The achievements of Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh aboard the Trieste resonate profoundly in our modern era, as humanity continues to face unprecedented challenges in ocean conservation. Their dive not only pushed technological limits but also offered a glimpse into a vast, mysterious world teeming with life. Both men dedicated their lives to advancing oceanography and inspiring future generations of explorers. Subsequent missions, such as James Cameron’s solo dive to Challenger Deep in 2012, owe much to the path paved by Piccard and Walsh.

As the Trieste sits in the museum, her story reminds us that exploration is a cornerstone of human progress. In the face of immense risks, Piccard and Walsh demonstrated the power of determination and collaboration. Their journey to the bottom of the world not only expanded our understanding of the ocean but also proved that no frontier is beyond our reach.

Leave a comment