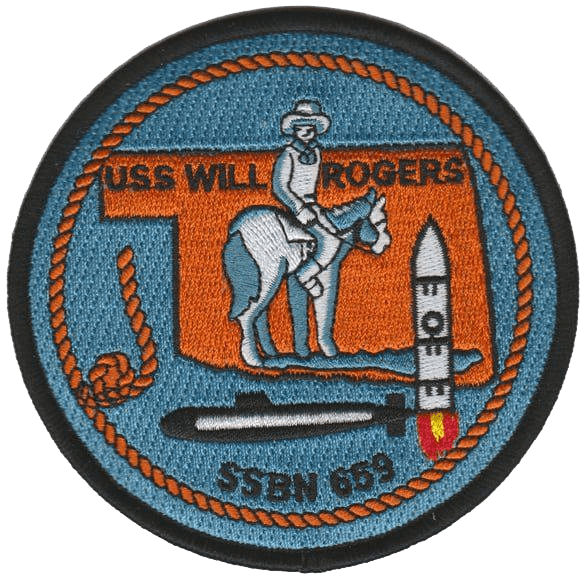

The USS Will Rogers, SSBN-659, was the last of the “41 for Freedom,” the great Cold War fleet of nuclear ballistic missile submarines that defined America’s undersea deterrent from the early 1960s through the 1980s. She was a vessel built for silence, vigilance, and patience, born into an age where peace depended upon the quiet readiness of men and machines deep beneath the sea. Her namesake, Will Rogers, was a man of wit and wisdom who once joked that he never met a man he didn’t like. The submarine that bore his name was built for a world that could not afford to test that philosophy too often.

Will Rogers the man was born on November 4, 1879, in Oologah, Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. He was a Cherokee cowboy, humorist, and social commentator who rose from the ranchlands to become one of America’s most beloved public figures in the early twentieth century. His rope tricks and quick wit carried him from vaudeville stages to the pages of newspapers across the country. Rogers’ plainspoken wisdom and gentle satire of politics and society earned him the affection of millions. He was also a serious advocate for common sense, humility, and civic duty, qualities that matched the spirit of the men who would later serve aboard the submarine bearing his name. Rogers died in 1935 in a plane crash in Alaska, alongside famed aviator Wiley Post, but his philosophy of good humor and quiet strength lived on, fittingly honored by a vessel that carried both peace and power beneath the waves.

The keel for the Will Rogers was laid down on March 20, 1965, at General Dynamics Electric Boat Division in Groton, Connecticut. She was the last of the Benjamin Franklin class, the final link in a long chain of fleet ballistic missile submarines that had begun with the George Washington class only six years earlier. These boats were the backbone of the United States’ nuclear deterrent, part of the triad that also included bombers and land-based missiles. At 425 feet in length and displacing about 7,320 tons when surfaced, she was a silent fortress capable of carrying sixteen Polaris missiles and later the improved Poseidon system. To the average citizen, her existence was a rumor or a line item in a congressional budget. To the sailors who served aboard, she was a home that never stopped humming, a steel womb floating in the deep with a single, terrible purpose.

The USS Will Rogers was launched on July 21, 1966, with Muriel Humphrey, wife of Vice President Hubert Humphrey, serving as sponsor. She was commissioned on April 1, 1967, and placed under the command of Captain R. Y. Kaufman for the Blue Crew and Commander W. J. Cowhill for the Gold Crew. Like all ballistic missile submarines, she operated on a dual-crew system to maximize her time at sea. While one crew patrolled, the other rested and trained ashore, ensuring that the submarine could spend most of her life where she was most effective: undetected in the deep ocean, holding a deterrent capable of ending civilization if deterrence failed.

Her first ballistic missile launch came on July 31, 1967, at the Atlantic Missile Range off Cape Kennedy, Florida. The missile soared clean and true, confirming her readiness to join the nuclear deterrent patrols. Later that year, she began her first strategic patrol. At that time, her missiles were Polaris A-3 models, each capable of delivering a nuclear warhead thousands of miles away with deadly precision. She joined the Atlantic Fleet and began operating out of her early homeport in Groton, Connecticut, before shifting forward to Rota, Spain. The move to Rota, completed in 1974, placed the Will Rogers closer to her patrol areas, allowing quicker turnaround between deterrent missions. For her crews, Rota meant long separations from home, short periods of liberty, and the constant rhythm of refit, patrol, and return. It was not a glamorous life, but it was one built on discipline, routine, and purpose.

The 1970s brought the transition from Polaris to the more advanced Poseidon C-3 missile. The Will Rogers underwent conversion at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, with the refit completed in February 1974. The Poseidon system allowed for multiple warheads, greater accuracy, and more reliable launch capability. It was part of the continuing evolution of the fleet that mirrored the technological arms race of the Cold War. While politicians and generals debated treaties, the crews of boats like the Will Rogers remained submerged, unseen, the quiet guarantors that no war would start without catastrophic consequence.

Following her refit, the Will Rogers conducted patrols from Rota and later from Holy Loch, Scotland, which became her forward base from 1978 through November 1991. Holy Loch was more than a port; it was a floating city of submarines, tenders, and sailors living under the constant gray skies of the Clyde. For over a decade, the Will Rogers slipped in and out of those waters, a shadow leaving port in the night and returning weeks later, her patrol completed without fanfare. The public rarely heard of her movements, and even many in the Navy knew only her number and class. Yet she and her sister boats represented the single most survivable leg of America’s nuclear arsenal. Should everything else fail, they would still be there, ready to ensure that no enemy would emerge from such a conflict victorious.

In May 1986, the Will Rogers conducted a Demonstration and Shakedown Operation (DASO) off the coast of Cape Canaveral, successfully launching a Poseidon C-3 missile. The test was a routine validation of the submarine’s systems and the proficiency of her crew. For the men aboard, it was also a chance to break the monotony of patrol life. A missile launch, even a test, was an awe-inspiring event. The boat would rise to periscope depth, the crew tense at their stations, and then the world would erupt in thunder as a missile burst through the ocean’s surface. Moments later, silence returned, leaving behind only the hum of machinery and the knowledge that everything had worked as designed.

As the Cold War drew to a close, the strategic landscape began to change. Arms reduction treaties, budget constraints, and shifting priorities meant that many of the older submarines were slated for decommissioning. By the early 1990s, the Ohio-class boats with Trident missiles had replaced the earlier Polaris and Poseidon fleet. On November 2, 1992, the Will Rogers was deactivated but remained in commission for administrative purposes as she entered the Ship-Submarine Recycling Program at Bremerton, Washington. On April 12, 1993, she was formally decommissioned and stricken from the Naval Vessel Register. Her scrapping was completed on August 12, 1994, marking the end of not just a ship but an era. With her went the last physical trace of the original 41 for Freedom that had stood watch for nearly three decades.

For the men who served aboard her, decommissioning carried mixed feelings. Pride in their service mingled with the quiet sadness of seeing their boat stripped and cut apart. Sailors form bonds with their ships that outsiders rarely understand. Each patrol, each watch, each mid-watch coffee shared with a shipmate in the wardroom or control room becomes part of a collective memory. When the Will Rogers was dismantled, she left behind more than steel. She left behind a generation’s worth of stories, laughter, fear, and the constant hum of the reactor that had been their companion in the dark.

The choice of Will Rogers as her namesake remains an interesting one. Most of the 41 for Freedom were named for statesmen, explorers, or patriots—men like George Washington, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton. Will Rogers was different. He was a humorist, not a politician; a philosopher of the people rather than a commander or conqueror. Naming a ballistic missile submarine after him suggested a subtle kind of hope, that even in an age of atomic anxiety, there was room for humanity, humor, and perspective. Rogers often reminded Americans to laugh at themselves and to remember their shared decency. It was a comforting thought for the crews who lived day to day with the knowledge that their mission, if ever executed in earnest, would mean the failure of civilization itself. The irony of a boat carrying such destructive power bearing the name of a man who devoted his life to uniting people through laughter was not lost on those who served aboard her.

The Will Rogers carried forward that paradox throughout her career. She was a weapon built to prevent war, a sword kept sheathed under the waves. Her mission was not to strike but to deter, and in that role she was entirely successful. The Cold War never turned hot, and the missiles she carried were never fired in anger. In that silence lay victory, though it was the sort that could never be celebrated with parades or medals. The work was monotonous, the conditions cramped, the stress constant. Yet for nearly twenty-six years, the men of the Will Rogers did their jobs with quiet professionalism, ensuring that deterrence held.

By the time she was dismantled, the world had moved on. The Soviet Union had collapsed, and the strategic balance that had defined her purpose no longer existed. Yet the legacy of the Will Rogers endures. She stands as a symbol of the strange logic of deterrence, where peace depended on preparedness for unthinkable destruction. Her story is part of a larger chronicle of Cold War endurance, technological innovation, and the moral weight of responsibility carried by ordinary men doing extraordinary duty.

In a way, Will Rogers himself might have appreciated the irony. He often said that people are just people, doing their best with what they have. The sailors who served aboard his namesake submarine lived that truth. They did their jobs not for glory or fame, but because someone had to stand watch, unseen and unheralded, so that others could live without fear. The USS Will Rogers may have been scrapped into recycled steel, but her spirit, like that of the man she was named for, remains embedded in the enduring story of America’s Navy and the long, uneasy peace she helped preserve beneath the waves.

The USS Will Rogers SSBN-659 Association Website

The USS Will Rogers SSBN-659 Facebook Page

Citations

- Naval History and Heritage Command. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships: Will Rogers (SSBN-659). Washington, D.C.: Department of the Navy. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/w/will-rogers.html

- “USS Will Rogers (SSBN-659).” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Last modified October 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Will_Rogers

- NavSource Naval History. USS Will Rogers (SSBN-659) Photo Archive. Accessed October 2025. http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08659.htm

- “USS Will Rogers (SSBN-659).” Navysite.de. Accessed October 2025. https://www.navysite.de/ssbn/ssbn659.htm

- “USS Will Rogers Veterans Association.” UssWillRogers.com. Accessed October 2025. https://usswillrogers.com/uss-will-rogers-info/

- “USS Will Rogers (SSBN-659).” HullNumber.com. Accessed October 2025. https://www.hullnumber.com/SSBN-659

- “Benjamin Franklin-Class Submarine.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Last modified 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_Franklin-class_submarine

- “USS Will Rogers – Protecting the Big Honest Majority.” The Lean Submariner (blog). October 12, 2019. https://theleansubmariner.com/2019/10/12/uss-will-rogers-ssbn-659-protecting-the-big-honest-majority/

- Defense Visual Information Distribution Service (DVIDS). “Poseidon C-3 Launch from USS Will Rogers (SSBN-659).” Image, May 20, 1986. https://www.dvidshub.net/image/9009667/uss-will-rogers-c3-launch

- GlobalSecurity.org. “Benjamin Franklin Class SSBN.” Accessed October 2025. https://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/systems/ssbn-640.htm

- Department of Energy. Ship-Submarine Recycling Program: Annual Summary. Washington, D.C., 1995.

- “Ship-Submarine Recycling Program: 1994 Completion List.” Naval Sea Systems Command Records. Puget Sound Naval Shipyard Archives, Bremerton, WA.

- “Will Rogers.” Oklahoma Historical Society Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Accessed October 2025. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=RO019

- Yagoda, Ben. Will Rogers: A Biography. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993.

Leave a comment